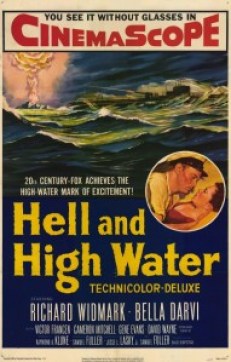

Starring Richard Widmark, Bella Darvi, Victor Francen, Cameron Mitchell, Gene Evans, David Wayne, Stephen Bekassy, Richard Loo

Starring Richard Widmark, Bella Darvi, Victor Francen, Cameron Mitchell, Gene Evans, David Wayne, Stephen Bekassy, Richard Loo

Directed by Samuel Fuller

Expectations: Low. This is Fuller’s least favorite film according to his book.

![]()

Hell and High Water begins in classic Sam Fuller style, hitting hard with a stunning image designed to immediately excite the viewer and grab hold of their attention. The particular image that opens this Fuller film is a giant nuclear explosion on a remote island (which is actual footage of a test blast by the military), and we’re quickly told via narration that it’s this explosion that the film is about. Sort of. The explosion is more like the catalyst to the film and its climax, but I guess you could say that the explosion informs the entire film and gives tension to the events presented within. That’s kind of a stretch though. This conflicted feeling I have is representative of how I feel about the entire film.

Going into Hell and High Water I had virtually no idea what the film was about. All I knew was that it was a Sam Fuller film, that it was something of a military film, that it was a bigger budget studio picture made as a favor, and that it was Fuller’s least favorite of his pictures. Like the opening explosion, the knowledge that Fuller didn’t like this one informed my viewing of the film. To my surprise though (and realistically I shouldn’t be surprised), Hell and High Water is pretty damn fun, and exceedingly well produced. It is Fuller’s first film in color, as well as his first CinemaScope film and he wastes no time in utilizing both to great effect.

Fuller was able to spend a couple of days on a real submarine before shooting the film and this experience resulted in Fuller adding a few elements to the picture. Coincidentally, these were some of my favorite aspects of the picture, as they felt real and very reminiscent of Fuller’s frank depiction of the reality of infantry life in previous films. When a crew member tries desperately to close the sub’s hatch as they perform an emergency dive, he gets his hand stuck in the closing hatch. In another movie with another director, our hero would have strode over and pulled the man out unscathed, spouting some bullshit line about having a close shave and to be careful next time. In Fuller’s film where a harsh reality is ever-present, the captain (Richard Widmark) does stride over, but instead calls for one of the crew’s knives and slices off the caught finger. No one in 1954 had to balls to put that in a movie except Sam Fuller, and that’s exactly why he’s one of my favorite directors.

Fuller was able to spend a couple of days on a real submarine before shooting the film and this experience resulted in Fuller adding a few elements to the picture. Coincidentally, these were some of my favorite aspects of the picture, as they felt real and very reminiscent of Fuller’s frank depiction of the reality of infantry life in previous films. When a crew member tries desperately to close the sub’s hatch as they perform an emergency dive, he gets his hand stuck in the closing hatch. In another movie with another director, our hero would have strode over and pulled the man out unscathed, spouting some bullshit line about having a close shave and to be careful next time. In Fuller’s film where a harsh reality is ever-present, the captain (Richard Widmark) does stride over, but instead calls for one of the crew’s knives and slices off the caught finger. No one in 1954 had to balls to put that in a movie except Sam Fuller, and that’s exactly why he’s one of my favorite directors.

Another key feature of the film is the use of the submarine’s red lights. During his stay on the real sub, Fuller noticed that they turned on red lights in order to get the crew’s eyes adjusted to the dark when they meant to surface at night. Many of Hell and High Water‘s scenes are shot with these red lights full on, including one mid-way through where Widmark helps the female scientist (Bella Darvi) to her cabin. He carries her into her cabin and places her in bed under the blood-red lights, and finally they embrace and kiss. The moment is a classic example of Fuller’s lack of subtlety, blasting red over a passionate moment, but it’s gorgeous and emphasized to great effect.

At its heart the film is nothing more than a big-budget action yarn and Fuller really does try to have fun with it. It never ceases to be entertaining, but those looking for the driving and pointed narrative of Fuller’s other pictures will be somewhat disappointed. Fuller took the project on as a favor and so it wasn’t a story that he originated or truly cared about. Still, he took it upon himself to re-write the script into something he could work with and it is filled with loads of great scenes and thrills.

One of the best, thrilling scenes is when Widmark and crew encounter a Chinese submarine hot on their trail. After a tense exchange with the ship’s Morse Code lights, the Chinese start firing torpedoes at them. This leads Widmark to order the crew to take the sub to the ocean’s bottom, and there they try their best to wait out the Chinese sub who has followed their lead and done the same. It’s a tense, nail-biting section of the film that works because of Fuller’s expert camerawork and the really outstanding special FX work. I know underwater footage of two submarine models from the 1950s doesn’t sound like a good time, so imagine my surprise when the models not only look great, but their movements feel realistic and full of weight. This easily could have been laughable, especially watching it nearly sixty years after release, but I’ll say it again: the submarines looked fantastic and the scene was incredibly tense.

Fuller’s bread and butter has always been his ability to realistically capture the interactions between a crew of men in his writing because of his experiences in World War II. Hell and High Water is no different and features a lot of great crew members with some enjoyable exchanges, but the problem here is that there isn’t anything that sets this one above, or even on the same level as, Fuller’s earlier films. As an entertainment picture solely it succeeds completely, but fans of Fuller will definitely find this one lacking a bit due to the director’s relation to the project. Fuller’s use of CinemaScope is quite good and the film is notable for being one of the first batch of films to use the format which debuted only the year before. Fuller effectively captured both the wide vistas usually associated with the format, as well as the tight claustrophobia of the submarine’s confined spaces. It’s no Das Boot mind you, but for the time I don’t think anyone could have done it better.